Paradox Noise

|

“YOUR ONLY CHANCE LIES IN PREVENTING THE ASSASSINATION OF PRESIDENT ABRAHAM LINCOLN . . .”

“What?” A burst of audio and visual static reduced reception to unintelligible noise. Then the paradox-generated interference was gone again, as suddenly as it had come. ” . . . Fourteenth of April at Ford’s Theater –” blast, crackle. “. . . you must be within two meters of the President . . . just before the bullet smashes into Lincoln’s brain. Your total window of opportunity will be three seconds.” – Fred Saberhagen’s After the Fact |

If the block universe view is correct, if time is “nothing but” a space dimension, then we should be able to travel in it. Leaving aside the fact that we don’t quite yet know how to do this (but see some of the books under references) shouldn’t time travel be forbidden by the paradoxes it would otherwise make inevitable? There are three kinds of paradox to consider:

Three kinds of paradox

Grandfather paradox

Why pick on grandfather? It seems that the only way to prove that time travel is impossible is to cite a case of killing one’s own grandfather. This incessant murdering of harmless ancestors must stop. Let’s see some wide-awake fan make up some other method of disproving the theory.

– 1933 letter to Astounding Stories, as quoted in Nahin’s Time Machines: Time Travel in Physics, Metaphysics, and Science Fiction

This is your classic time travel paradox: you go back in time and kill your grandfather: now where did you come from? Do you vanish immediately (in a puff of logic) or slowly fade away? We assume that you kill your unfortunate ancestor before he engenders your father/mother, that there are no paternity issues, and so on.

This would appear to be a refutation of time travel: how is time travel possible if the time traveler could cause himself never to have been born?

If we had no idea how to make a time machine we could relegate this to the world of complete fantasy, but in a 1949 paper Gödel showed that there are solutions to Einstein’s General Relativity in which time travel is possible:

By making a round trip on a rocket ship in a sufficiently wide course, it is possible in these [rotating] worlds to travel into any region of the past, present, and future, and back again, exactly as it is possible in other worlds to travel to distant parts of space. This state of affairs seems to imply an absurdity. For it enables one, e.g., to travel into the near past to those places where he himself lived. There he would find a person who would be himself at some earlier period of his life. Now he could do something to this person which, by his memory, he knows has not happened to him. [as quoted in Nahin’s Time Machines].

As General Relativity is our best current theory of gravity, this implication cannot be dismissed out of hand. Matt Visser has noted that in General Relativity anything that is big enough and spinning fast enough, seems to generate a time machine. Per his Lorentzian Wormholes: From Einstein to Hawking:

General relativity is in fact infested with peculiar geometries that seem to produce time machines.

For instance, in Frank J. Tipler’s paper “Rotating Cylinders and the Possibility of Global Causality Violation” Tipler argues that if you are fortunate enough to be in possession of a large, rapidly spinning cylinder and a high speed rocket, you could travel backwards in time by rocketing around the cylinder in the right sense. This is similar to the way Superman used to be able to travel to future or past by circling the Earth rapidly enough (clockwise for future; counter-clockwise for past?).

The well-known science fiction writer Larry Niven wrote a riposte to Tipler, a short story with the same “Rotating Cylinders and the Possibility of Global Causality Violation” title. In Niven’s story an evil empire tries to make use of a Tipler-style time machine to win a war. It turns out that the universe:

- doesn’t care for time machines &

- cancels out evil empires that try to make use of them.

This is all well and good (unless you are an evil emperor of course) but seems inelegant somehow: something as important as the self-consistency of the universe should be guaranteed by the laws of nature themselves; you shouldn’t have to call in the Time Police [their motto: you won’t just wish you had never been born!] to fix things.

Bootstrap paradox

This is a second order of paradox: the time traveler’s travels are self-consistent enough, but he does something like: go into the future to look up a patent, come back to his present, and file the patent. This is part of the action in Robert Heinlein’s The Door into Summer. Who wrote the patent?

Self-writing patents violate the second law of thermodynamics: you can’t create order without expending energy. At some point, someone or something has to actually do the work. It is occasionally possible to trick someone else into paying for your lunch, but at some point every lunch has to be paid for.

Zombie paradox

|

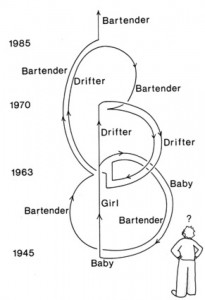

Robert A. Heinlein’s All You Zombies

A Paradox can be paradoctored! “I’m My Own Grandpa” “I know where I come from, but where do all you zombies come from?” (Drawing is from Kaku’s Hyperspace: A Scientific Odyssey Through Parallel Universes, Time Warps, and the 10th Dimension |

A (slightly) subtler paradox is provided by Robert A. Heinlein’s “All You Zombies”. Here our hero turns out to be, thanks to a time machine and a sex change operation, his own mother and father. The story seems to be self-consistent. And we know where he came from. And we would rather not think about his chromosomes & any lethal recessives he might have. But the whole thing just doesn’t compute.

This represents a third kind of paradox in time travel stories, where it is clear that paradox of first or second kind has been avoided only by the most aggressive possible paradoctoring by the author: you can practically smell the burning rubber as the author twists and turns to avoid various plot holes. It is clear the characters are Zombies, helpless puppets of their author. Stories like this often end with the line:

But the time traveler had caused what he had set out to prevent!

At which point the reader may be tempted to wonder: but what if the traveler hadn’t been a complete lackwit / simpleton / dizzard / ninnyhammer / chucklehead / lummox / mooncalf?

Any resolution of the paradoxes associated with time travel should not only avoid paradoxes of the first and second kind; it should do so in a way that requires no contrivance, that leaves the actors with at least the appearance of free will.

Resolution of the paradox

Is it possible for a time traveler to avoid these three paradoxes in a way that is consistent with current physics?

Matt Visser, cited above, proposed four methods of getting rid of time machines or at least bringing them under control:

- Radical rewrite — time travel is possible; rethink everything!

- Novikov’s consistency conjecture — the universe is consistent; inconsistent alternatives are forbidden.

- Hawking’s chronology protection conjecture — consistent or not, time travel is forbidden.

- Boring physics conjecture — “a pox upon all nonstandard speculative physics”: why are we thinking about time machines when we could be thinking about global warming?

The first we really can’t say anything useful about: our physics might need a radical rewrite but:

- it has been giving pretty good results so far, and

- in any case we can’t say anything useful about this possibility until we know what changes are proposed.

The third, forbidding time travel, has the merit of being simple. But it leaves unexplained why/how time travel is forbidden. It seems overkill to bring in an extra postulate just to kill off time travel. Again, if time travel is forbidden, that should be something that follows from the laws of physics themselves.

The fourth is less acceptable than the third. Hawking’s conjecture imposes a solution by fiat; alternative #4 is to pretend there is no problem.

The second alternative is the one we will focus on here. Our assumption will be that there is only one universe and only self-consistent solutions are allowed. We will solve for temporal trajectories using the rules for sound waves in violins: in a violin, only those sound waves/harmonics are allowed which fit exactly into the violin. In the universe, only those paths are allowed which fit exactly into the universe.

There are two levels at which we can attack the problem:

- Using classical physics, including general relativity, but not including quantum mechanics.

- Using quantum mechanics.

But the billiard ball had caused what it had set out to prevent

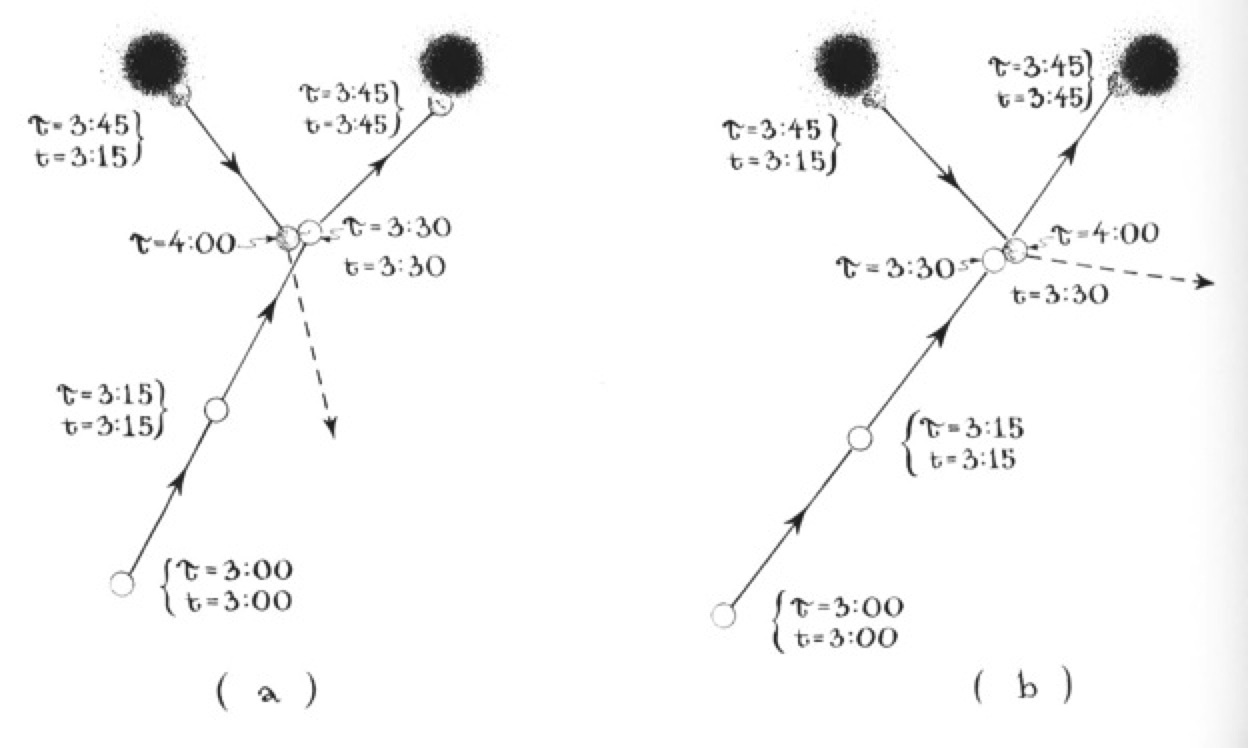

We will start with the classical mechanics case, as described by Kip Thorne in his Black Holes and Time Warps: Einstein’s Outrageous Legacy. We check a wormhole out of lab stores, one with a future end and a past end. Anything that goes into the future end comes out of the past, and vice versa.

There are some trifling practical problems which we will not trouble ourselves with:

- how to build such a wormhole,

- how anyone less elastic [and inured to pain] than Wile E. Coyote could get thru it,

- and whether the manuals needed to operate this safely might themselves be so massive that they would collapse into a black hole.

Per Thorne, Polchinski proposed the following paradox: we fire a billiard ball at the future mouth, aiming it so precisely that when it comes out of the past mouth it will hit itself coming into the future mouth knocking itself aside just enough that it will miss when it comes out of the past mouth so that it can go into the future mouth unimpeded so that it will again knock itself aside just enough …

You see the problem. And so did Thorne’s grad students Echeverria and Klinkhammer. They worked out that there exist self-consistent trajectories for the billiard ball. In these when it comes out of the past end, it strikes itself a glancing blow so that it is knocked aside just enough that it only strikes itself a glancing blow. This then is the prediction: the billiard ball will be struck a glancing blow by itself.

One troubling feature of their solution is that while normally in classical mechanics for one billiard ball with fixed starting point and starting velocity there is only one outcome, there are now multiple solutions: the glancing blow can glance in a number of different ways.

Still, ambiguity is to be preferred to paradox.

But the wave function had caused what it had set out to prevent

But we know that classical mechanics is not the last word. Real particles are not billiard balls; they do not have well-defined shapes and positions; they are quantum mechanical, and their shapes, positions, and speeds are fuzzy. What happens if we try to create a paradox using particles described by quantum mechanical wave functions?

This problem has been solved by Pegg and also by Greenberger & Svozil. The basic result in both papers is the same: a quantum wave function going thru a time machine cancels out any parts of itself that might create a paradox.

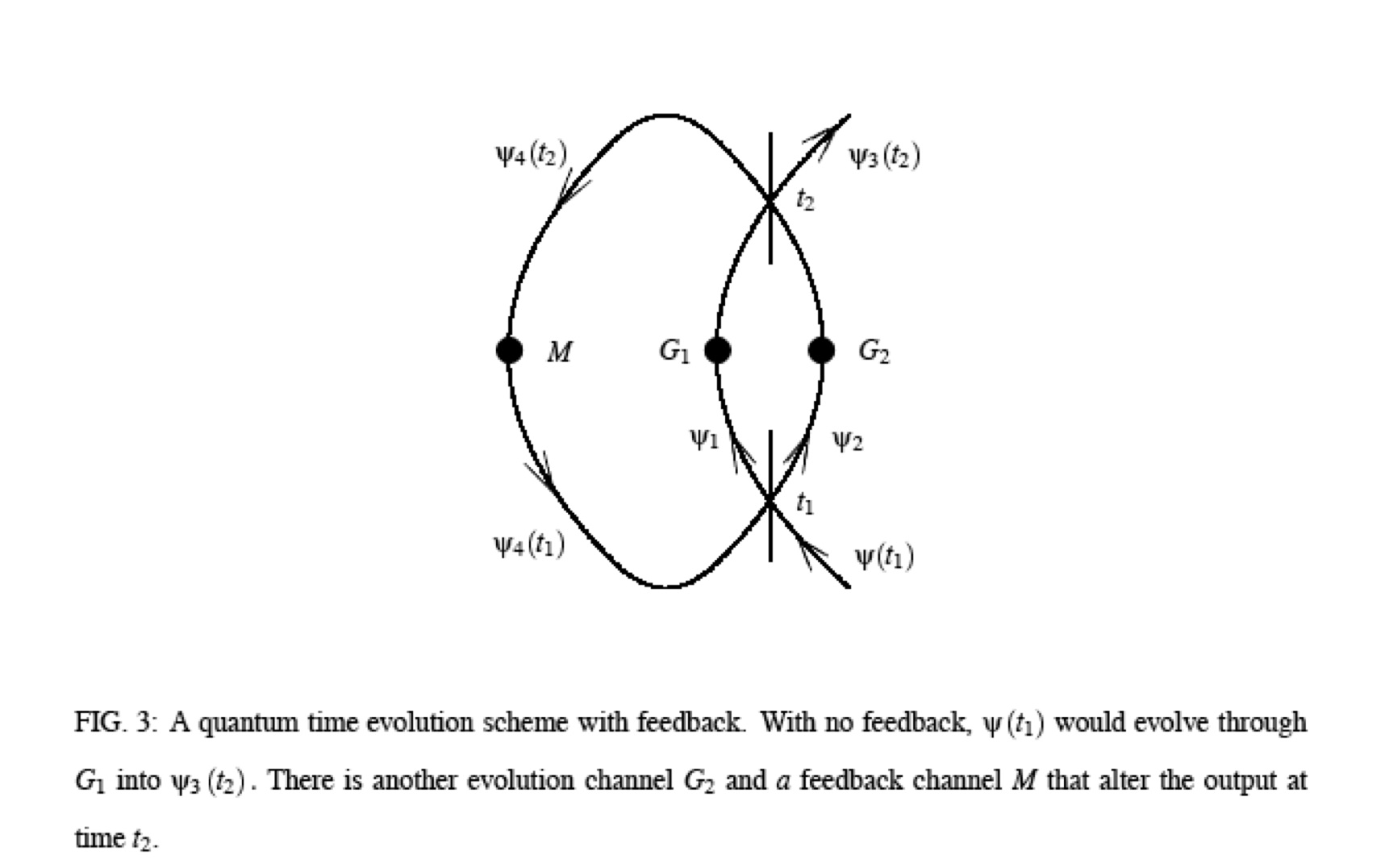

I’ll follow the Greenberger & Svozil treatment here. The illustration is from Greenberger & Svozil, of a particle coming in at the bottom right. It is split into two parts, Ψ1 and Ψ2, by a half-silvered mirror at t1. The two parts travel along, meeting at a 2nd half-silvered mirror at t2. Part of the wave function, Ψ3, is sent into the future to the top right, the other part, Ψ4, heads back to the past, where it meets up with Ψ1 at t1.

Abstract time machine

Presumably Ψ4 is carrying whatever information we want to use to play games with the past. The matrix M is used to imprint information on to Ψ4, useful stuff like “buy Microsoft” or “sell Microsoft” [these experiments don’t pay for themselves!].

Can this create a paradox?

Greenberger & Svozil do the not trivial but not terrible maths and find that if you do try to create a paradox, the paradox is self-canceling. As they put it:

According to our model, if you travel into the past quantum mechanically, you would only see those alternatives consistent with the world you left behind you. In other words, while you are aware of the past, you cannot change it. No matter how unlikely the events are that could have led to your present circumstances, once they have actually occurred, they cannot be changed. Your trip would set up resonances that are consistent with the future that has already unfolded.

There is a natural interpretation of paradox noise in terms of path integrals: if we compute the quantum wave function by taking the sum over all paths from initial wave function to final, then we arrive at the Pegg/Greenberger & Svozil result by throwing out all paths that are self-contradictory while summing over the rest.

We will use Saberhagen’s term for this interference: paradox noise.

Implications of paradox noise

In other words, [the time traveler’s] life as observed from other reference frames must be consistent with his own observations just as spatial observations must be consistent. This does not necessarily mean [the time traveler] can never appear in his own past, but rather that he cannot change that past after he has experienced it.

— Catherine Asaro “Complex Speeds and special relativity” Amer. J. of Physics v64 p421

What would paradox noise look like?

Let’s suppose all of the above is the case, and that you can construct a time machine, at least in the sense of a machine that sends information backwards in time, a “time phone”.

You – purely in the interests of research – decide you will send information back to yourself about tomorrow’s share prices, something simple like “buy Microsoft” or “sell Microsoft”. This works well enough at the start, but now you are rich and your purchases are big enough to have an impact on the share price. Now, when you buy, the price goes up enough that you would have chosen to sell instead (& vice versa). And now all your “time phone” shows is a: “burst of audio and visual static” — the problem Saberhagen’s time travelers had.

No question of volition is involved: whether the paradox would have been created intentionally or inadvertently is not relevant.

But, the restrictions created by paradox noise only apply to players. A watcher might have access to information not available to a player, creating a duality between knowing the future and acting to change it.

If your personal future is defined as the space of events whose outcome you don’t know and your personal past the space of outcomes you do know, then what is future to you (if acting as a player) might be past to another (acting as a watcher). One man’s future could be another man’s past.

Note of course that if a watcher tries to sneak information over to a player, the watcher becomes by that act a player and governed by player rules. You can’t fool mother nature; don’t even try.

Does paradox noise avoid the paradoxes?

- The Pegg and the Greenberger & Svozil approaches include only self-consistent paths by construction. If you are going to encompass the death of a grandfather either he had already done that which he needed to do progeny-wise or he wasn’t really your grandfather or you missed or …

- There would still have to be work done to create a patent, but the work might be done in the future with the patent being filed in the past. To avoid self-consistency problems, the person writing the patent in the future would have to be kept carefully ignorant of the results of his or her own labor, even if the rest of the world knew. The normal straightforward relationship between increasing entropy and the direction of time would require re-examination: see for instance Schulman’s Opposite Thermodynamic Arrows of Time.

- Writers could relax: their characters would not be able to get the information needed to create a paradox in the first place. In fact a Chekhov or a Maupassant might find interesting plot possibilities in the fact that paradox noise denies information only to those who might use it in paradox-creating ways, whether they mean to or not.

What is paradox noise good for?

So, you can’t learn about the future when your learning about the future would cause you to change it. Seems very frustrating, except: often the most important thing you need to know about the future is that you don’t know about it. You might not be able to figure out the share price of Microsoft, but you would at least know that it was in flux and that your actions would have a significant impact on it. That information alone could easily be worth the price of admission.

Or, as friend Socrates might have put it, `the recognition of ignorance is the beginning of wisdom’.